names by new invaders

The Vikings, Hull, and place names have a long history. Indeed, it was these invaders who gave us our very first name: WYKE – a sort of ‘maiden name’ of our city, if you like! They knew a good place for a port if anyone did. Wyke means ‘creek’ and was probably what we now call ‘Old Harbour’ (at the mouth of the River Hull near The Deep). This might have been after 866 AD when the Danes took control of Jorvik (York) and made it a key trading centre. The Vikings themselves, did not settle in the Wyke area – it was too marshy at that time. Nevertheless, the Humber Estuary was a major sailing route for the Viking invaders and traders.

Actually, although we call them Vikings that was not the name they gave themselves. They might have preferred Norsemen – people of the north. The ‘Vik-‘ element is similar to our Wyke and alludes to the fjords of Norway. I highlighted the ‘-ing’ suffix in Part Two of this series when we examined Anglo-Saxon names. I firmly linked the ‘-ing’ ending to kin as in kinship, family group or people. One example being Hastings – the followers of Haesta.

Put together, the name Vik-ings is reference to the ‘people of the fjords’. The Norwegian Vikings are often mixed up with the Danes. It was the Norwegians who generally attacked Scotland and Ireland; whilst the Danes raided England. Before going into detail about particular local Viking place names, it is worth spending some time telling the back story of these plunderers.

THE RAPE and PILLAGE: Going Berserk

There were two distinctive stages to the Viking attacks on Britain: raid and invade. The earliest one was the savage assault on Lindisfarne (793 AD) when they killed the Celtic monks and ransacked their rich possessions. Isolated monasteries were ladened with loot, undefended and easy targets for hit-and-run raids against unarmed friars.

Such notorious events sent waves of terror throughout Britain and European Christendom. It was the start of the Viking Age (793-1066). The Danes were Pagans in combat with Anglo-Saxon Christians. The raiders believed that their god rewarded brave fighters who died in battle – Valhalla (Odin’s Great Hall of the Slain). Not only England suffered, but the whole of Europe was in fear of the ‘scourge from the North’. The popular image of the Vikings is of them ‘raping and pillaging’ everywhere they went. They are depicted as wild savages with lots of blood on their hands.

These Viking raids, however, were not coordinated by one central power or king. Instead, they tended to separate into tribes or groupings – probably centred on a family (or kinship) network. One such were known by their apparel ‘behr sekr’ – in other words, they wore bear skins. Well, after all, it gets cold up there in Scandinavia. The Berserkers were fierce warriors who just kept on slaughtering their enemies even after they had fallen. They hacked away until their bodies were cut to pieces. Even their fellow Vikings gave them a wide berth and left them to slaughter the enemy unhindered. The word ‘berserk’ subsequently came into English and now means ‘to go violently crazy’.

GLOBAL EXPLORERS and TRADERS

Despite their bloody reputation, the Vikings had some remarkable expertise that are worth highlighting. They were second-to-none with their boat-building and navigational abilities. Indeed, they may well have been the first Europeans to set foot in Iceland, Greenland and North America (c1000 AD – perhaps in Newfoundland which they called Vinland) – centuries before Columbus set sail (1492).

Russia got its name directly from the Vikings. ‘Rus’ is an Old Norse (ON) word for ‘the men who row’. The country of Belarus also derives its name from the invaders. With their long ships, they navigated their way down the Volga River to the Caspian Sea (to trade with Baghdad) and along the Dnieper River to the Black Sea – sometimes hauling their boats overland. They then had access to Constantinople and even formed the first Varangian (Greek name for the Vikings) Guards. In essence, they were a band of mercenary thugs who formed a protective wall around various (unpopular) Byzantium Emperors from the 10th century – over the decades – until they converted to the Orthodox Christianity and merged into that society.

Academics disagree as to why the once-peaceful Vikings left their homelands. Some speculate that their own country was too rocky, covered in forest, and had poor sandy soil. Others argue that Scandinavia was over-populated (yet short of females). Equally, only the eldest son could inherit farmland – so younger brothers had to clear off elsewhere.

From the British perspective, the second stage of conflict with the Vikings was much more powerful and long-lasting. Instead of isolated raids, 57-years after the Lindisfarne carnage, a highly organised fleet of some 350 well-armed Danish long ships sailed up the Thames (850) – determined to invade and stay this time. Unlike previous attacks, they set up camp and wintered on the Isle of Thanet, Kent. Their plan was to bide their time and then conducted their major campaign in the springtime. A series of savage battles took place over the next few decades in which the invaders conquered large parts of England. Other Danish forces joined their ranks, and they evolved into what became known as the Great Heathen Army.

Britain was attractive to the Vikings because it had good soil for farming and rearing animals. England was divided into mini-kingdoms who squabbled over each other’s territory. It is worth highlighting, however, the Vikings did not just chop down people, but also used their axes to chop down trees to clear woods and build farmsteads. Yes, they had a sword in one hand, but a spade in the other. Generally, the invaders settled down into farming the land they had taken.

The Danes conquered large areas of the country and forced the Anglo-Saxons to retreat into Wessex. The invaders went on to attack this kingdom in the winter, when least expected to do so, and made even greater gains. Things were looking very bad for the English race.

ALFRED the GREAT (849 – 899)

The English rarely give the title of ‘Great’ to anyone. But they did to Anglo-Saxon Alfred. Why? Because when Christian England and the English language were close to extinction, he ‘saved our bacon from the Danish’ (sorry about that awful pun). It was a last-minute decision to make 21-year old Alfred the king (871). He ordered a retreat even further south west to the Somerset marshes. There, he re-built and re-grouped his forces. He was intelligent and had a master plan.

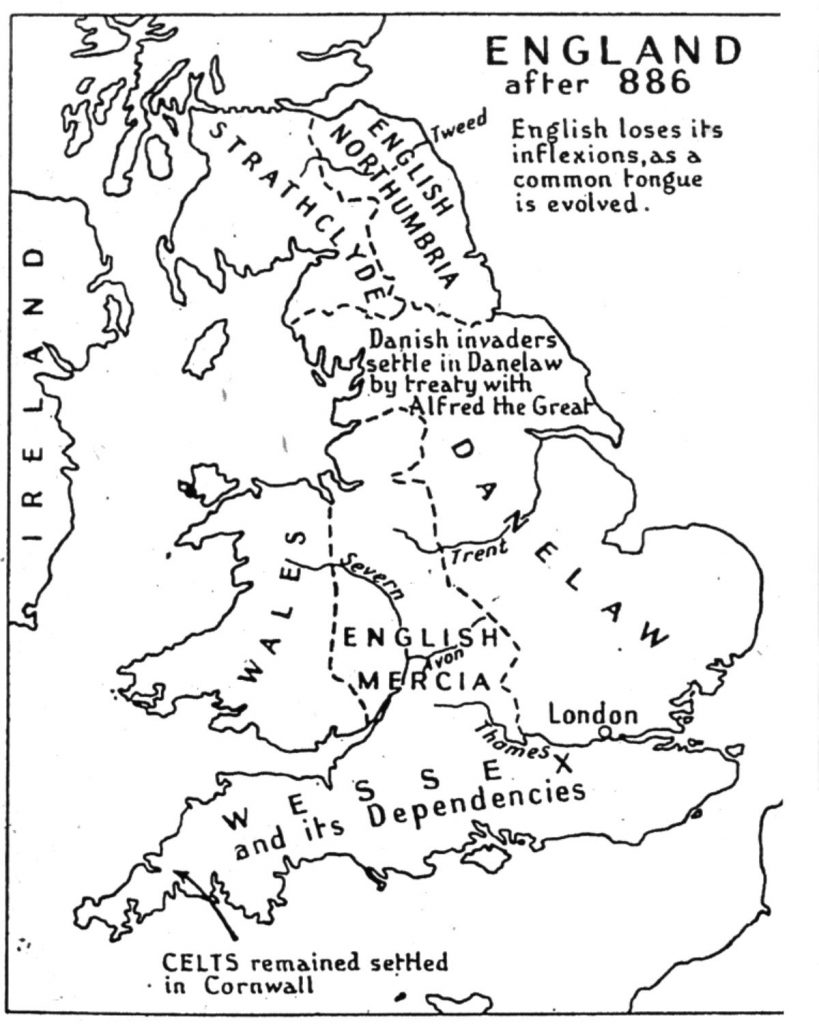

Under Alfred’s inspired leadership, the Anglo-Saxons made a great comeback. In May 878 he beat the Danish King Guthrum at the battle of Edington and forced him to sue for peace. Wessex was saved. Guthrum and 29 of his followers were also baptized as Christians. England was then divided between the Danes and Anglo-Saxons by a line running roughly from London to Chester – as agreed in the Wedmore Peace Treaty. Danelaw was established to the northeast of that line (the A5 roadway – former Roman Watling Street). It is still a linguistic division in the study of local dialects to this day.

Alfred went on to build up the number of English naval vessels. They tackled the Vikings at their own game – even before they landed. The best method of defence is attack – and it worked.

After beating another invading Danish army in Kent, Alfred re-captured London. A further peace deal was struck with the Danes (886). Alfred established such a powerful military machine that it lived on long after his death in 899 (aged 50). Anglo-Saxon forces continued their run of victories. In 911, Rollo the Ganger was about to reinforce the Danes with his army. When he heard that his beleaguered Danish countrymen were getting beaten, he got scared. He changed course (and history) to land in Northern France, beat the Frankish forces and created what we now know as Normandy (a corruption of Norsemen) – but that is another story for Part Four.

VIKING PLACE NAMES:

As with the Anglo-Saxons, the Danes also had a preference for places having common endings. As always, there is much uncertainty about the true origin of any names. I have, therefore, had to indicate my lack of knowledge with a question mark (?) when I am unclear. Please excuse the number of (?)s. The most well-known Viking suffix is ‘-by’. So I will begin with those and then list the rest alphabetically.

-by (habitation or settlement) = Anlaby (Anlef’s farmstead); Derby (village of the deer. Note: Derbyshire is the only county name linked to the Vikings); Ferriby (village near the ferry); Garrowby (Gerwarth’s farm); Grimsby (perhaps a Danish fisherman called Grim settled here. Note: Grim is a similar name to the Brothers Grimm and their fairy-tales); Kexby (Kek’s farm or an overgrown farm); Risby (farm near a clearing); Selby (? settlement by sallow or willow trees); Sewerby (Siward’s farmstead); Skidby (Skyti’s or a dirty farm); Thirtleby (Thorkel’s farmstead); Wetherby (wether sheep farm near a bend in the River Wharfe); Whitby (Hviti’s or white farm); Willerby (Wilgardi’s farmstead). Note: the legal term ‘by-laws’ comes from this ON suffix and refers to laws made by a local authority.

-bald (?building?) = Newbald (new building); Thorngumbald (settlement near thorn bush – the official emblem has a Viking helmet with wings).

-coates (cottage) = Dairycoates (dairy cottage); Sculcoates (Skuli’s cottages – OScand); Southcoates (Soti’s cottage – not a cottage to the south, as I first assumed).

-fleet (stream – Anglo-Saxons also used same suffix) = Broomfleet (?stretch of the river – Ouse/Humber); Faxfleet (? it might be a person’s name or near a stream where coarse grass grows); Marfleet (? pool or small stream flowing from mere); Ousefleet (? nearby river name). Note: London’s famous Fleet Street is built over a small tributary of the Thames.

-foss (waterfall) = Wilberfoss (Wilburg’s ditch). Note: Many centuries later, William Wilberforce’s family originated from this village and their surname was derived from it.

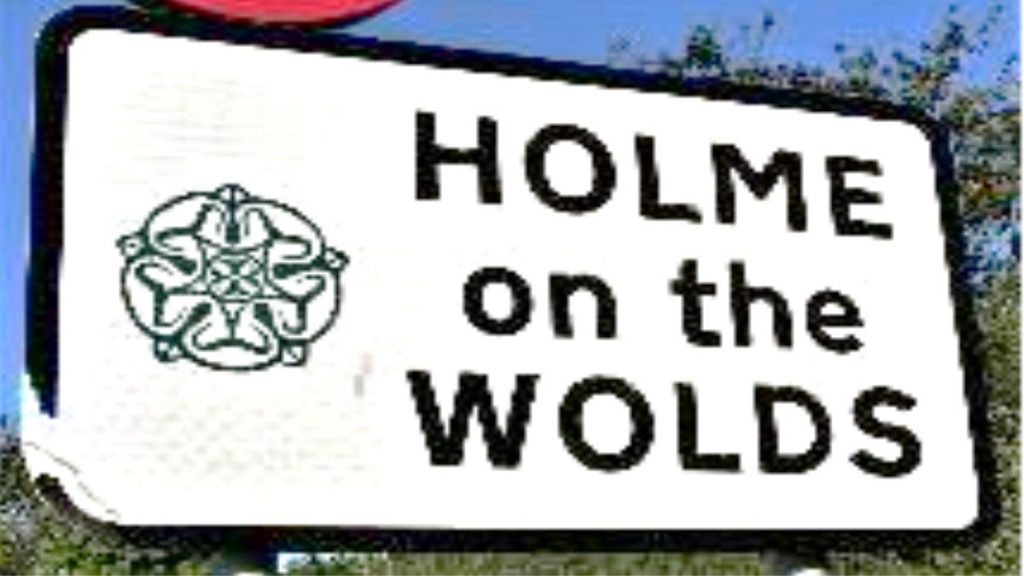

-holme or –holm (high land surrounded by water meadow or a dry spot in a marshy area) = Benningholme (Benna’s water-meadow – Anglo-Scandinavian name); Bransholme (Brand’s water meadow or wild boar?); Holme-on-Spalding-Moor (hill in a marshy area); Holme-on-the-Wolds (spur of land – obviously in the Wolds); Nunburnholme (?at the streams + link to a nearby Benedictine Nunnery); Waxholme (place where bees’ wax is produced).

-ness (generally refers to a nose-shaped promontory) = Gunness (Gunni’s headland – promontory into River Trent); Holderness (Danish word ‘hold’ meaning a nobleman with considerable holdings of land – Spurn Point looks like a long nose); Skegness (Skeggi’s headland or beard-shaped headland).

-sea (large body of water?) = Hornsea (‘Horn’ perhaps in the sense of a projecting piece of land and the ‘sea’ is a reference to the Mere); Kilnsea (pool near the kiln); Withernsea (OE or ON Witthorn’s dairy farm); Skipsea (lake upon which a ship could sail).

-stead (place) = Ganstead (similar names found in both Denmark and Norway); Winestead (not traced by me: anyone out there know?).

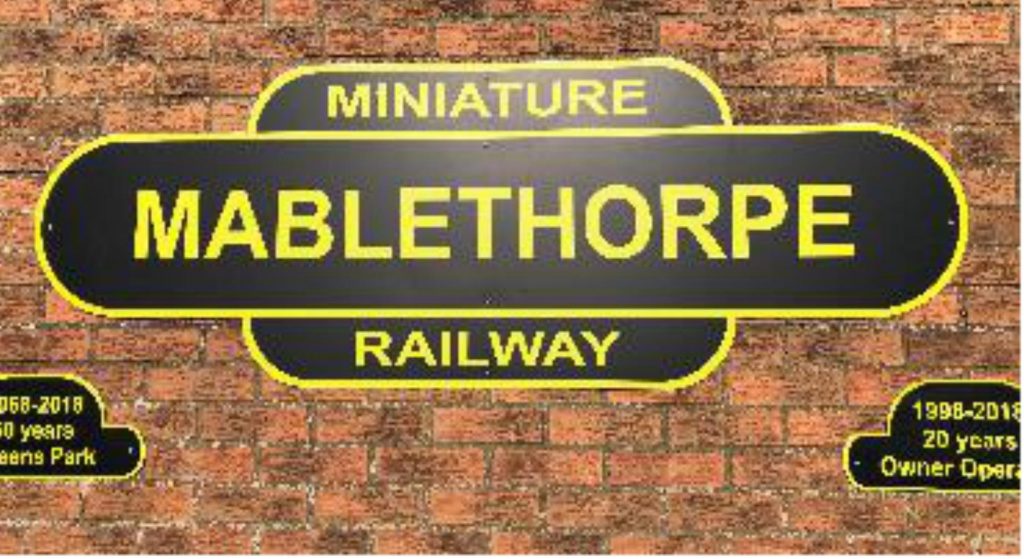

-thorpe (secondary farm) = Cleethorpes (Clee’s farm); Danthorpe (village of the Danes); Everthorpe (upper village); Fraisthorpe (Freisting’s village); Fridaythorpe (?Frigg’s farm or people who worshipped Freya); Mablethorpe (Malbert’s outlying farm); Scunthorpe (Skuma’s farmstead); Tibthorpe (Tibbe’s village).

-toft (house) = Blacktoft (black house or ground); Langtoft (long or narrow house).

-wick (usually means a farm associated with a particular product – mainly dairy in this region) = Atwick (Atta’s dairy farm); Burstwick (Brusti’s dairy farm); Catwick (the dairy farm of Catta); Kilnwick (Cylla’s dairy farm); Owstwick (east dairy farm); Welwick (dairy farm near the spring).

-worth (enclosure) = Eppleworth (apple wood); Epworth (? unsure).

Although the following place names are not Viking, their ‘-gate’ suffix was still used long after they themselves had faded into history. -gate (road / walk) = Blackfriargate (from Dominican friars – an intellectual order who wore black robes); Lowgate (? maybe as opposed to High Street); Posterngate (back or side route into the walled town); Whitefriargate (after the Carmelite monks with their white garb).

VARIED VIKING NAMES:

The Viking suffixes generated a variety of interesting clusters. There are, however, some unique places in our area that are worth listing:

Kirk (church) – Kirk Ella (disputed meaning – might be woodland clearing with a church?).

Skirlaugh: ‘bright clearing’. During this Anglo-Scandinavian period, much of Holderness was still fairly marshy; thus this ‘bright clearing’ might have referred to the land being on higher ground (like a –holme). Not 100% certain about this one.

Swine (creek or channel) – not linked to pigs.

Thwing (narrow strip of land) a bit like the word strap / thong. Similar names in Denmark. Equally, it might be ‘a local court or meeting place’ – like Thing in Iceland: the national legislature or Parliament of Iceland.

West Ella (church to the west? uncertain). Note: J.Marr & Son (Hull trawler owners) had a large fleet they named with the ‘-ella’ suffix = Benella; Cordella; Farnella; Junella; Kirkella; Lorella; Northella; Southella; Swanella; and Westella etc.

Wetwang (meeting place or place of justice) – this was a field where criminals were summoned for trial (perhaps similar to Thwing).

As well as their own names, the Vikings influenced some pre-existing Anglo-Saxon names. One local example is Skerne – near Driffield. Originally, this place was ‘Sherne’ (Sh- not Sk-). One meaning gives this name as ‘shining river’. The trouble being that there is no actual river running through Skerne itself – but the River Hull is nearby. Anyway, that aside, when the Vikings came along with their own Norse language, they pronounced it with “Sk” at the start – thus, Skerne.

Coincidentally, the same process occurred with the actual River Sherne. It flows from Trimdon to the Tees up near Darlington. Its earlier Anglo-Saxon name was something like ‘Sherne’ (the shining river). It also became Skerne under Danish influence. Place names can have a chequered history.

But let’s conclude by returning to our hero Alfred. As well as saving the country, he also made a contribution to some place names in our area. He was a man of foresight and intelligence. He had to ensure the safety of his people from future attacks. As well as improving his naval forces, he vastly improved defences around the country – and this is where place names are important. Not always – but often enough – where you see a ‘-borough’ or ‘-brough’ ending, it will be thanks to Alfred.

These suffixes are derived from the Old Germanic word ‘-burgh’ (as in Edinburgh) and mean ‘fortress’ or ‘walled collection of buildings’. It seems that when the ‘-borough’ suffix was added to an established place name, due respect was paid to the previous existing names or tribal origins. Here is Alfred’s contribution to certain place names:

-borough / -brough (fortress) = Aldbrough (old stronghold); Alkborough (Aluca’s or Alca’s hill); Brough (covered in Part One of this series); Flamborough (ON: ‘spear shape’ that juts out into the North Sea); Flixborough (Flik’s stronghold); Gainsborough (Gegn’s fortress); Londesborough (Lothaen / Lodenes – Old Danish personal name meaning hairy or shaggy); Middlesbrough (it was midpoint between two major Benedictine Priories at Durham and Whitby); Scarborough (Skarth’s stronghold); Stallingborough (Saint Avbur’s resting/burial place).

These fortresses or enclosed villages were where rural workers could seek refuge and safety for their family, goods and cattle if a Viking raiding party landed. No village would be more than 20 miles from such a ‘burgh’. When the Danes attacked again in 892, they made little if any advance. This was almost one hundred years since the atrocious attack on Lindisfarne. So the Anglo-Saxons, after muddling through, got their act together eventually.

In the fourth and final part of this place name series, I will examine the contribution of the Norman conquerors. After all, it was they who compiled the Domesday Book (1086) – probably the first time many of our place names were written down. We will then go on to explore place names in the British Empire and beyond.